The Missing Literary Link: Tolkien, Language, and Forgotten Myths

Originally appearing in the Apex Publications blog (now defunct), April 2013

So we all know that Tolkien wrote the seminal work of modern fantasy, known collectively as The Lord of the Rings, but divided across three books: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King, which are each subdivided into several smaller books within those books. If you haven’t heard of this guy or these books, at least tell me you’ve seen the movies.

The Lord of the Rings is an amazing tale of the triumph of good over evil, the power of friendship and loyalty, the tenacity of the underdogs, and is shot through with enough myth and poetry to choke a horse. A really, really big horse.

I once read an internet rumor (so very trustworthy, right?!) that Tolkien actually believed the stuff he was writing, which I found to be a little odd because elves and hobbits and orcs and …really?

But here’s the thing. It’s true.

After a fashion.

See, Tolkien was a philologist, which is a fancy word for someone who studies language. Specifically, language as used in literature and the historical record. Tolkien studied English and you might think that English has been studied and what could there possibly be to learn about it? But there you’d be mistaken. The English language has a fascinating history and it an amalgam of layers of languages both domestic and foreign. One of the biggest and most far-reaching change to English came with the Norman Conquest of 1066 when English got in bed with French.

(Think about this, then discussing food if it is in the barnyard it is a cow but if it is on the plate it is beef, derived from bœuf, the French word. Which illustrates the language variations of those who served and those who were served. The French were in charge, the English got relegated to servants or worse.)

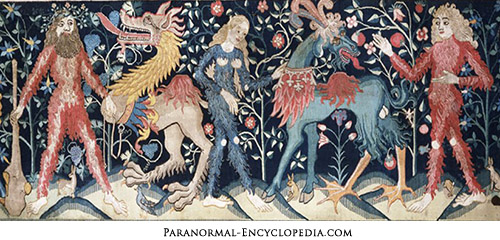

The English lost a great bit of their language in this time, and it has since gotten further mingled and mixed with a plethora of others like German, Scandinavian, and Dutch, not to mention all those colonies and whatnot. But aside from a loss of original language, the early English also had a great deal of their culture swept away by Christianity. The old myths were replaced or blended with Christian stories and parables. Tolkien was a devout and lifelong Catholic and also dear friends with C. S. Lewis, well known for his Christian writing. In the Narnia books, it almost seems like Lewis took a Christian story and applied it to a more pagan style of myth (and seriously for years, even though I went to Catholic school, I utterly failed to see the Christian symbolism in the Narnia books and totally thought they were pagan…and therefore awesome).

Tolkien’s approach was different. In Prof. Tom Shippey’s book, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, he dissects Tolkien’s purpose in creating Middle Earth and the stories set there. In Tolkien’s mind, he was recreating a set of myth stories that we should have had and would have had if history had gone a bit differently. Among many things, Tolkien was an expert on Beowulf, one of the few extant stories to come out of pre-Christian England, and even then it has its roots in other northern European cultures. Tolkien applied his love of history and language and Beowulf and blended it with the style of myths found in pre-Christian Scandinavia. He based most of his initial plotting on the language itself.

The Hobbit starts with the line, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” and Tolkien literally started from that line, jotted down in the margin of a paper he was grading. Going on to define what a hobbit was and why they lived in holes and what sort of holes they were basically fills up the first quarter of the book. And it was so wildly popular, his publisher begged for a sequel.

By this time, Tolkien had moved onto trying to capture his thoughts on the language similarities across northern and western European cultures. All of them use the world “elf,” for example. The forms of the word vary, but not by much and the context is the same. An elf is humanoid, but not human, otherworldy, immortal, occasionally treacherous /mischievous/untrustworthy, etc. Tolkien concluded that there must have been elves in the world. Realio, trulio elves. Because these cultures would not have thought up the same world and meaning were they not based on some kind of reality. So, what happened to the elves?

He sought to answer that question through The Lord of the Rings, but not before attempting to publish his long and elaborate Scandinavian-style myth cycle about the elves known as The Silmarillion and failing miserably because The Silmarillion would have been a great read for the 8th century but not so much for the 20th. Still, he went on working on it until his death and it was finally published posthumously, although most people still can’t make head nor tails out of its archaic language and literary devices and the complexities of characters and storylines that put most soap operas to shame. But it serves his purpose of providing a sprawling myth-cycle to rival any pagan pantheon and provides the framework for understanding everything you need to know about the elves of Middle Earth. To quote Shippey from The Author of the Century, “[Tolkien] was also reaching back to an imaginative world which he believed had once really existed, at least in a collective imagination.” (XV)

Tolkien reconstructed whole mythologies from a single word. My favorite: “wodwos” (Shippey, 82). Tolkien translated this “wood-wose” into the modern English “Wood-troll” and further extrapolated that the road where his office was located, “Woodhouse,” might have been a misheard/misspelled version of “wood-wose,” and therefore long, long ago that road might have been named in warning of dangerous creatures which lurked in the forest rather than some house built in the woods. It is this dimension to Tolkien’s work that sets him apart from nearly every other fantasy writer that tried to follow in his quest-tale footsteps.

Tolkien fills in for us our missing literary link, the set of myths and legends lost to time and conquest. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are English to their core, drawing on an English history so far eclipsed even the English don’t remember it. The Riders of the Mark, for example, were taken from the nearly forgotten history of central England that was once known as Mercia. Most texts from this period and this area were written in the West Saxon dialect which told Tolkien that these people (from whom he himself was descended) did not have a strong literary history although their language did survive somewhat into the modern era if one knew where to look. So if one were sufficiently versed in Old English languages, one would find that all the names given to the Riders of Rohan (and their horses) were totally derived from Mercian, not West Saxon! I don’t know if there is anyone on the planet besides Tolkien who would have known this, but he was that committed to his craft and to leaving very special Easter Eggs to those who would read his work.

It’s no small wonder that authors have spent the last several decades trying to recapture that magic. But they aren’t going to come close because what they are writing is merely a reflection of Tolkien’s world, not what he was doing which was trying to shed light upon a world might have been- compete with language, customs, histories, and myths. And that’s the beauty of myth. “Myths are what is always available for individuals to make over, and apply to their own circumstances, without ever gaining control or permanent single-meaning possession.” (Shippey 192)

There are a lot of missing literary links out there in the world, a lot of erased histories. If we really want to be like Tolkien, we shouldn’t be retracing his steps through Middle Earth, we should be out there uncovering wood-woses and recreating the world of the forgotten kingdoms and making over some myths.

Books you should totally read:

Bridgeford, Andrew. 1066: The Hidden History of the Bayeux Tapestry. London: Walker & Company, 2005. (I recommend this with some hesitation, dude knows his stuff but he quotes himself from his other books and articles way too much, but it is a fascinating read and perspective on early medieval English history.)

McWhorter, John. Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue. New York: Gotham Books, 2008.

Shippey, Tom. J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Shippey, Tom. The Road to Middle Earth. New York: Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin, 2003.

Recent Comments